Weingarten Rights

NLRA – Section 7:

"Employees shall have the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid and protection"

NLRB v. Weingarten, Inc. 420 U.S. 251 (1975):

The employer violated [Section] 8 (a) (1) of the National Labor Relations Act because it interfered with, restrained, and coerced the individual right of an employee, protected by [Section] 7, "to engage in … concerted activities for … mutual aid or protection," when it denied the employee's request for the presence of her union representative at the investigatory interview that the employee reasonably believed would result in disciplinary action.

Weingarten Rights. Most union members have heard this term. Many shop stewards have the right to protect their members because of it. But what is the origin of these rights? What lies behind one of the most significant labor law rulings in recent history? For thirty years, Weingarten has been an often-used word in the vocabulary of union advocates.

Here is the story:

J. Weingarten, Inc. operated a large chain of convenient stores, several of which allowed customers to purchase packaged meals. In June 1972, Ms. Leura Collins, a lunch-counter clerk at Store No. 98 in Houston, Texas, was called into the manager's office and interrogated by her manager and a loss prevention investigator employed by the store. Unknown to Ms. Collins, this investigator had been observing her for the past two days on the basis of a report that she was stealing from the register. Although this particular investigation uncovered no evidence of wrongdoing on Ms. Collins' part, another manager learned (from a coworker) that she "had purchased a [$2.98] box of chicken … but had placed only $1.00 in the cash register."

During the interview, Ms. Collins, a member of Retail Clerks Local Union No. 455, requested several times that her steward or another union representative be present. When questioned about the chicken, Ms. Collins replied that she only took a dollar's worth, but was forced to use a large-size box since the small ones were not available. The investigator went to confirm this; upon his return he "told Collins that her explanation had checked out [and] that he was sorry if he had inconvenienced her, and that the matter was closed."

It was at this point that Ms. Collins finally broke down, exclaiming that the only thing the company ever gave her was a free lunch. Hearing this, the manager and the investigator were surprised, since Store No. 98 had no such policy. Once again Ms. Collins was interrogated, once again she requested representation and once again it was denied. The investigator then asked her to sign a statement that claimed she owed the company $160 for those "free" lunches. She refused. In Store No.2, where she had previously worked [1961-1970], free lunches were policy. It was later learned that other J. Weingarten employees, including the manager, took "free" lunches, since the company had no official policy that forbade it, a fact confirmed to the investigator who then ended the interview.

Upon leaving, Ms. Collins was asked by the manager "not to discuss the matter with anyone because he considered it a private matter between her and the company [and] of no concern to others." However, Ms. Collins reported this incident to her union and an unfair labor charge was filed.

The Purpose

One vital function of the steward is to prevent an employer from coercing or intimidating employees into confessing misconduct, especially in situations where the supervisor (or any other employer representative) engages in interrogatory techniques.

The NLRA protects union concerted activities, which includes a member's right to request union representation during investigatory interviews. This right was recognized in 1975 with the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in NLRB v. J. Weingarten. (420 U.S. 251)* and became known as a member's Weingarten Right.

*Note: This opinion was delivered by Justice William Brennan and was joined by Justices Douglas, White, Marshall, Blackmun and Rehnquist [the current Chief Justice]. The dissenting opinion was filed by Chief Justice Warren Burger and joined by Justice Powell.

A lone employee, confronted by the employer's investigation and the possibility of discipline, may be either too afraid to face accusations, too inarticulate to accurately explain, or simply to uniformed to raise extenuating factors. A knowledgeable union representative could assist this employee by drawing out favorable facts or applicable mitigating circumstances.

A tangible knowledge of Weingarten is vital, since it allows the steward to:

- Serve as a (non-silent) witness to this interview

- Contradict a supervisor's possibly false account of said interview

- Prevent intimidating tactics or confusing questions by supervisor

- Prevent the member from making self-incriminating statements or admissions

- Advise the member, under certain circumstances, to deny everything

- Warn the member about losing his or her temper

- Discourage the member from informing on others, i.e., co-workers

- Identify any extenuating or mitigating factors that could benefit the member

The Investigatory Interview

Weingarten Rights can be invoked ONLY in an investigatory interview, which occurs when:

- Employer Representatives (Supervisor, Manager, et. al.) question an employee about specific conduct or to obtain information that could be used as a basis for discipline.

- As a result of the above, the employee has a reasonable belief that the interview could result in discipline or some other adverse consequence. Example: an employee being questioned about an accident would be justified in fearing that he or she might be blamed.

Of course, not every interaction between employee and supervisor is an investigatory interview; for example, a supervisor speaking to a subordinate about a particular job performance. While the supervisor may no doubt question the worker about his or her performance, the likelihood of discipline is not the issue. Both parties are merely engaged in a work-related conversation – there is no investigation.

However, this workshop conversation could suddenly acquire an entirely different demeanor should the supervisor becomes hostile or the questioning turns into suspicion. In this case, any employee may become fearful; at this point would require union representation.

Yet, when a supervisor (or any agent of the employer) calls an employee into the office to warn, reprimand or impose discipline already decided, this is not – according to the NLRB* – an investigatory interview, since employee conduct is not being questioned, but rather has been observed and is being acted upon.

* Baton Rouge Water Works, 246 NLRB 995 (1979)

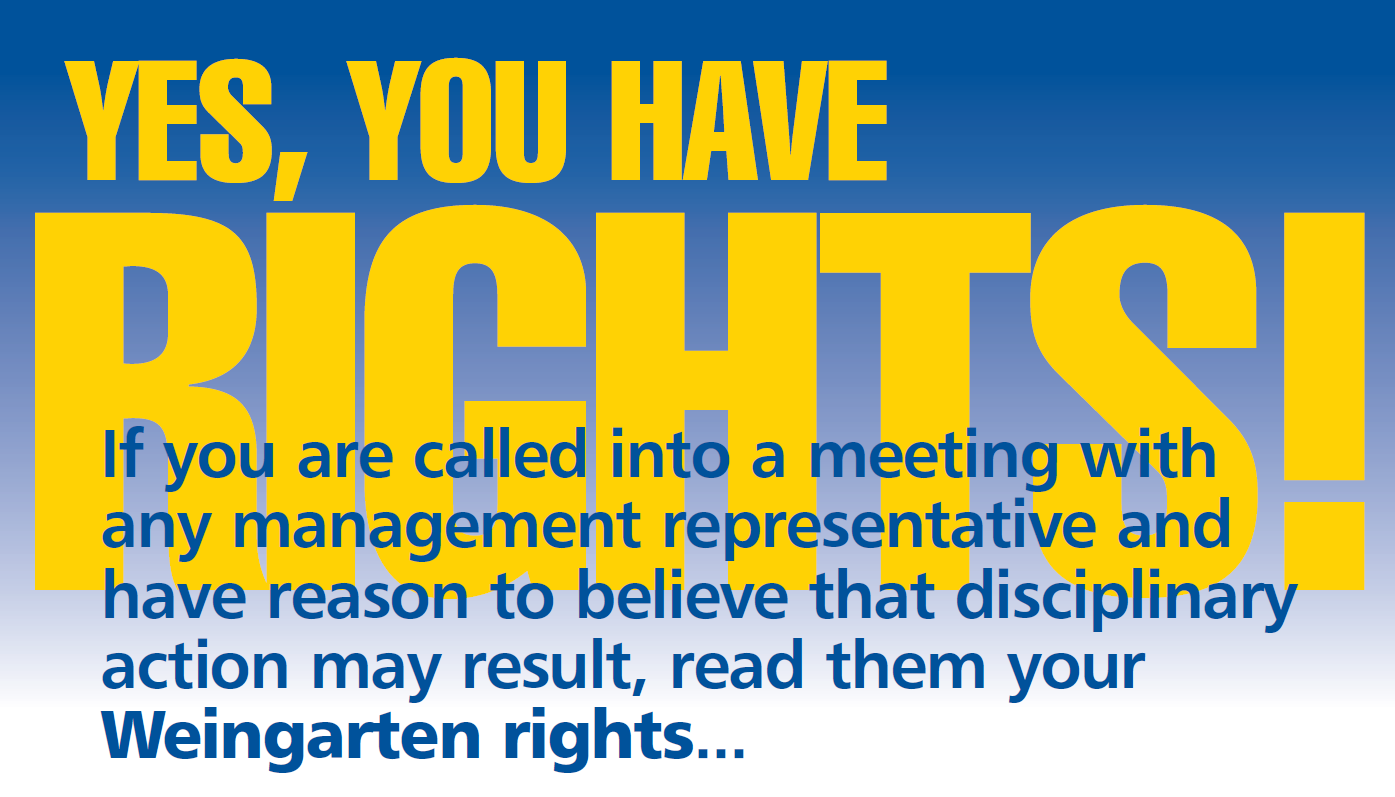

Educating Members

Unlike Miranda, another landmark Supreme Court case, Weingarten does not require notice at the time of questioning – or, in this case, an investigatory interview. This means that the Employer is not required to inform the employee that he or she has a right to Union representation. For the union and the steward, this means educating their membership by explaining these rights. Many local union contracts contain Weingarten in their language, such as this example:

The employer recognizes the employee's right to be given representation by a steward, or a designated alternate, at any investigatory interview. The employer will remind the employee of this right at the time that the employer requests the investigatory interview.

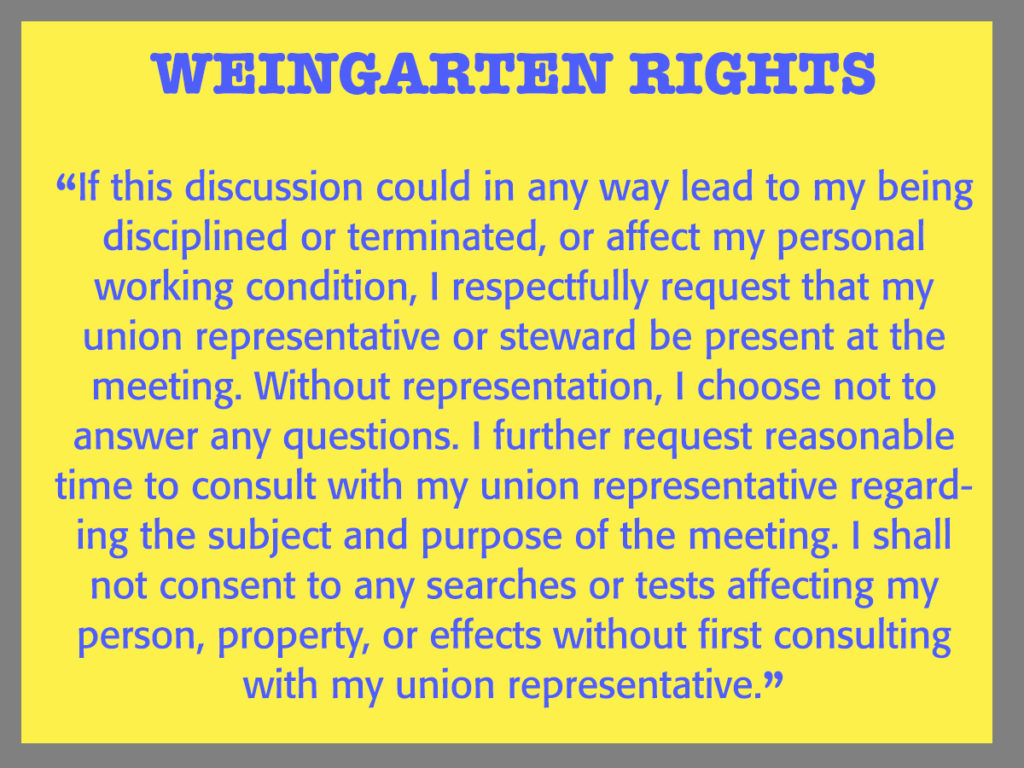

Many local unions provide their members with wallet-sized cards that read:

If this discussion could in any way lead to my being disciplined or terminated, or affect my personal working conditions, I respectfully request that my union representative, officer, or steward be present at this meeting. Until my representative arrives, I choose not to participate in this discussion.

Weingarten and Public Employees

The original applications of Weingarten covered only those employers under the National Labor Relations Act; therefore, it did not address public employers. However, each state has its own laws for public sector employees – and, each state will have different views on the right to union representation. For example, California public employees have the same rights during an investigatory interview, as do private sector employees. In any case, public sector employees are protected by the due process tenets provided in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the U.S. Constitution.

Download Weingarten Cards Here